RBT Skill Acquisition – Domain C of the Task List

RBT Skill acquisition is at the heart of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA). As a Registered Behavior Technician (RBT), one of your primary responsibilities is to implement programs designed to teach new behaviors and skills to your clients. These may include communication, social skills, daily living tasks, academic abilities, or play behavior. Whether you’re helping a child with autism learn to request items using picture cards or supporting a teen in acquiring vocational skills, RBT skill acquisition tasks are fundamental to meaningful progress.

Domain C of the RBT Task List (2nd edition) outlines 12 key sub-tasks (C-1 to C-12) that guide how RBTs prepare, teach, reinforce, and generalize skills. From understanding the essential components of a teaching plan to implementing strategies like discrete trial teaching (DTT) and ABA prompting and fading, this domain offers the backbone of therapeutic service delivery in ABA settings

Table of Contents

C-1: Identify the Essential Components of a Written Skill Acquisition Plan

Before an RBT can implement any teaching, they must first understand the structure of a skill acquisition plan (SAP). Before teaching begins, assessment plays a key role — see our Assessment module (B-1 to B-3) to learn how teaching plans are informed. These plans are created by a supervising behavior analyst and outline everything needed to teach a specific skill. Key components often include:

- The skill or behavior being taught

- Operational definition of the target behavior

- Teaching procedures (e.g., prompting method, reinforcer delivery)

- Materials required

- Mastery criteria

- Data collection instructions

- Generalization and maintenance plans

For example, a SAP may target increasing eye contact in a 5-year-old child with autism. The plan might specify using a least-to-most prompting strategy, delivering reinforcement in ABA immediately after eye contact is made, and collecting frequency data across 10 trials. As the foundation of the RBT Task List, RBT Skill Acquisition tasks must be implemented exactly as written to ensure consistency.

As an RBT, your job is to follow the plan as written and alert your supervisor if anything is unclear. Implementing incorrect procedures can lead to inconsistent data and stalled progress. A common mistake is skipping over materials or modifying prompts without authorization.

Tip for new RBTs: Create a quick checklist from the SAP before each session to ensure all steps and materials are covered.

C-2: Prepare for the Session as Required by the Skill Acquisition Plan

Preparation is key to executing effective skill acquisition sessions. RBTs are expected to review the SAP, gather materials, and set up the environment before working with the client. This task also involves checking previous session data, understanding which skills are in acquisition or maintenance, and preparing reinforcement systems.

Let’s say you’re teaching a child to label body parts using picture cards. Before the session, you’d ensure all cards are available, tokens or reinforcers are ready, and the session area is free from distractions. You’d also review data from the last session to identify which cards the child responded to independently.

Failing to prepare can lead to wasted time, ineffective teaching, or increased client frustration. For instance, not having a preferred reinforcer ready may reduce motivation and engagement.

RBT preparation tips:

- Keep materials organized and labeled by skill

- Use a tracking sheet to confirm what’s needed for each session

- Double-check reinforcer preferences before starting (they may change day to day)

C-3: Use Contingencies of Reinforcement

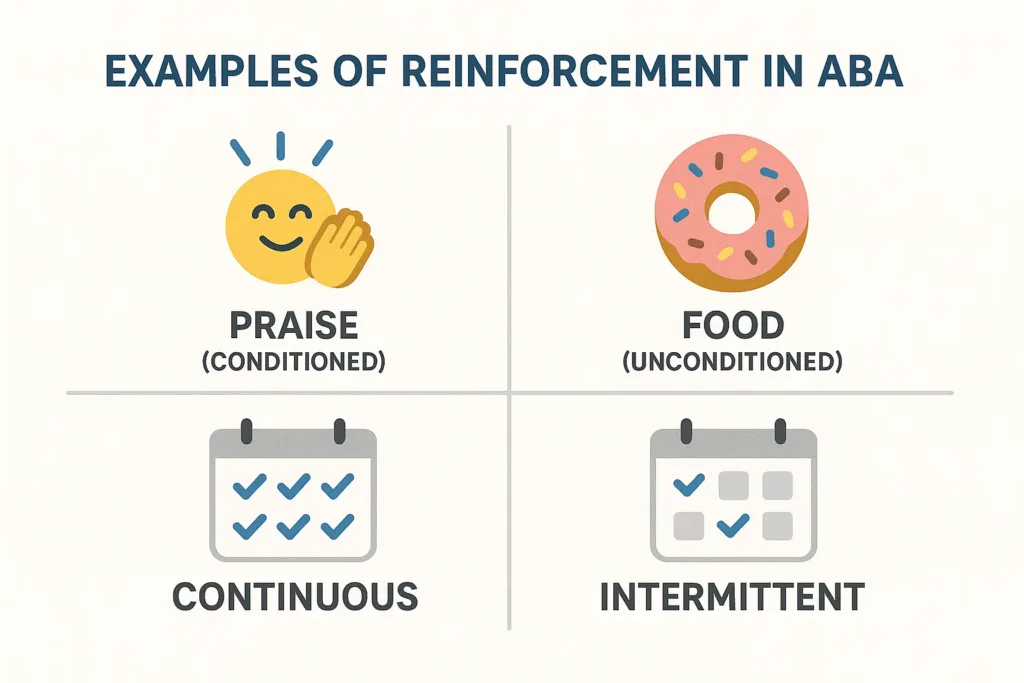

Reinforcement in ABA is the engine of learning, driving behavior change and supporting skill acquisition. RBTs must apply both conditioned and unconditioned reinforcers, using appropriate schedules of reinforcement to support the learning process.

Types of reinforcement include:

- Unconditioned (primary): naturally reinforcing, like food or water

- Conditioned (secondary): learned, like praise, tokens, or access to a toy

Schedules of reinforcement can be:

- Continuous: every correct response is reinforced (ideal for new skills)

- Intermittent: only some correct responses are reinforced (used for maintenance and generalization)

For example, teaching a child to say “more” during snack time might start with continuous reinforcement (e.g., giving a cracker every time they say the word). Over time, this may be faded to an intermittent schedule to promote independence.

Common mistake: Reinforcing incorrect or off-task behavior by accident — such as giving attention or a break when a client yells. Always pair reinforcement directly with the target behavior and deliver it immediately.

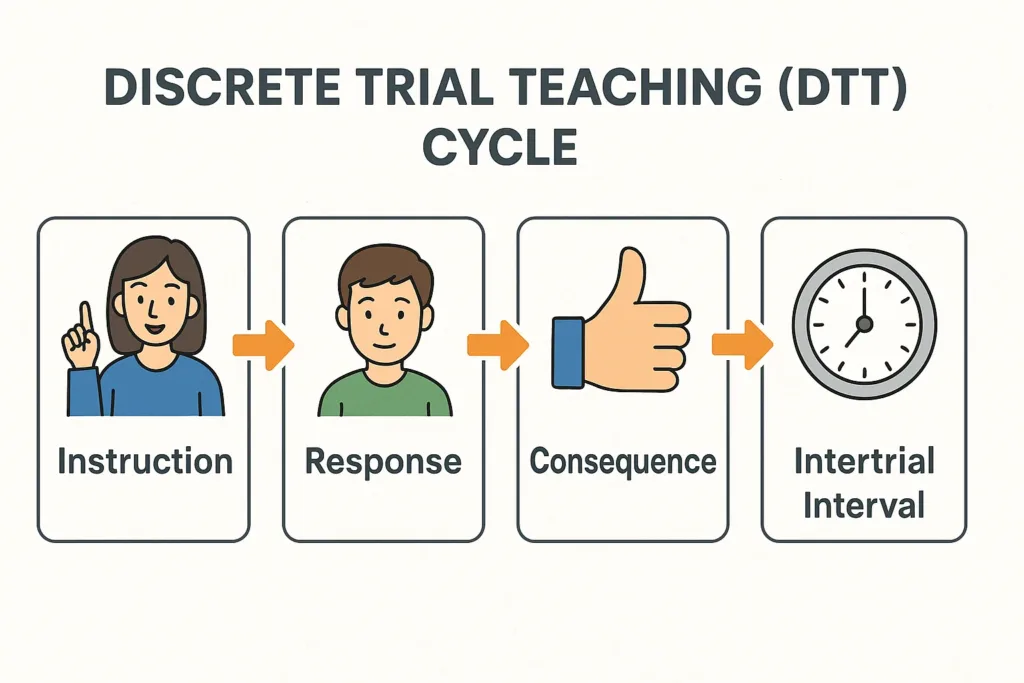

C-4: Implement Discrete-Trial Teaching Procedures

Discrete Trial Teaching (DTT) is a highly structured instructional format that breaks learning into small, manageable parts. Each trial consists of:

- An instruction or SD (e.g., “Touch your nose”)

- A response (e.g., client touches nose)

- A consequence (e.g., praise or reinforcer)

RBTs are responsible for delivering consistent trials, prompting as needed, and recording data for each attempt.

A DTT session for teaching color identification might involve 10 trials of “What color is this?” using red, blue, and green flashcards. The RBT provides a prompt if the child doesn’t respond or responds incorrectly, then delivers reinforcement for a correct or prompted response. After several sessions, the prompt is faded, and independence increases.

RBT tips for effective DTT:

- Use clear, concise language

- Avoid repeating the SD multiple times

- Provide immediate, enthusiastic reinforcement

- Record data in real-time

Common error: Delivering inconsistent prompts or reinforcement, which confuses the learning process.

C-5: Implement Naturalistic Teaching Procedures

Naturalistic teaching, often referred to as incidental teaching or natural environment teaching (NET), focuses on embedding learning opportunities into everyday situations and client-led interactions. Unlike discrete trial teaching (DTT), which is highly structured, naturalistic teaching leverages the client’s interests and motivation to guide instruction.

For example, if a child reaches for a toy truck, the RBT might hold it and prompt the child to say “truck” or “I want truck” before handing it over. The reinforcer (the truck) is directly tied to the behavior (the request), making the teaching moment more meaningful and functional.

RBTs using naturalistic teaching must:

- Be observant of client interests

- Wait for naturally occurring teaching moments

- Prompt as needed, and fade prompts when possible

- Reinforce responses naturally and immediately

Real-world scenario: A 6-year-old client loves building blocks. During play, the RBT pauses the activity and prompts the child to request “block” using a speech-generating device. When the child responds appropriately, they are given the next block to continue building.

Mistakes to avoid:

- Over-prompting or turning the interaction into a DTT-like format

- Missing teachable moments by focusing too much on materials or data sheets

- Using reinforcers that don’t match the context of the activity

Naturalistic teaching is ideal for generalization, social interaction, and early language skills. It also increases motivation and makes learning more fun and engaging.

C-6: Implement Task Analyzed Chaining Procedures

Chaining is used to teach complex behaviors by breaking them into smaller, teachable steps called a task analysis. Each step in the sequence is taught and reinforced systematically until the client can complete the entire chain independently.

There are three main types of chaining:

- Forward chaining: Teaching starts with the first step and moves forward (e.g., first step in hand washing: “turn on faucet”).

- Backward chaining: Teaching starts with the last step, working backwards (e.g., last step: “dry hands”).

- Total task chaining: Teaching all steps in the sequence during each session.

Example: Teaching a child to brush their teeth.

- Forward chaining: Teach “pick up toothbrush” first. Once mastered, teach “apply toothpaste,” and so on.

- Backward chaining: The RBT completes the entire sequence until the final step, prompting the child to “rinse and spit.” Once that step is mastered, the RBT fades assistance on the previous steps.

Practical tips:

- Always follow the written task analysis from the supervisor

- Use appropriate prompting and fading strategies

- Reinforce each successful step or the full chain (depending on the method)

Common mistake: RBTs sometimes deviate from the task analysis or help too much, which can lead to prompt dependency.

Internal link: Next Module: Behavior Reduction

Future blog idea: “How to Use Forward vs. Backward Chaining in ABA”

C-7: Implement Discrimination Training

Discrimination training teaches clients to differentiate between stimuli and respond only to the correct one. It helps build critical learning skills, such as recognizing letters, following verbal instructions, or identifying emotions.

In a basic discrimination training setup:

- A discriminative stimulus (SD) is presented (e.g., “Touch red”)

- Multiple stimuli are shown (e.g., red card, blue card)

- The client is reinforced only for selecting the correct stimulus (red)

Example: Teaching a child to identify animals. When shown a picture of a cat and a dog and given the SD “Touch cat,” the child must respond by touching the cat image. Reinforcement follows correct responses.

RBTs implement discrimination training using:

- Errorless teaching in early stages (prompting correct response)

- Prompt fading as the client becomes more accurate

- Random rotation of SDs to prevent rote memorization

Mistakes to avoid:

- Using unclear or inconsistent SDs

- Reinforcing incorrect responses

- Failing to mix up the stimulus presentation

Discrimination training is foundational for many skills — from academic performance to safety awareness — and must be implemented with care and precision.

C-8: Implement Stimulus Control Transfer Procedures

Stimulus control transfer is the process of shifting control of a behavior from a prompt to the natural discriminative stimulus (SD). The goal is for the client to respond independently to naturally occurring cues.

For instance, during early instruction, a child may be prompted to say “hi” when a peer walks into the room. Over time, prompts are faded until the presence of the peer alone becomes the SD, and the greeting happens spontaneously.

Steps involved:

- Use prompts (e.g., gestural, verbal) to guide behavior initially

- Fade prompts systematically (least-to-most or most-to-least)

- Reinforce correct responses as control transfers to the SD

Example: An RBT teaching a child to respond to “What’s your name?” may begin by whispering the answer. Over sessions, the whisper fades until the child answers independently.

Mistakes to avoid:

- Removing prompts too quickly, causing frustration

- Keeping prompts too long, leading to prompt dependency

- Not reinforcing correct unprompted responses

Mastering stimulus control transfer ensures the client can respond appropriately in real-life settings, not just training sessions.

C-9: Implement Prompt and Prompt Fading Procedures

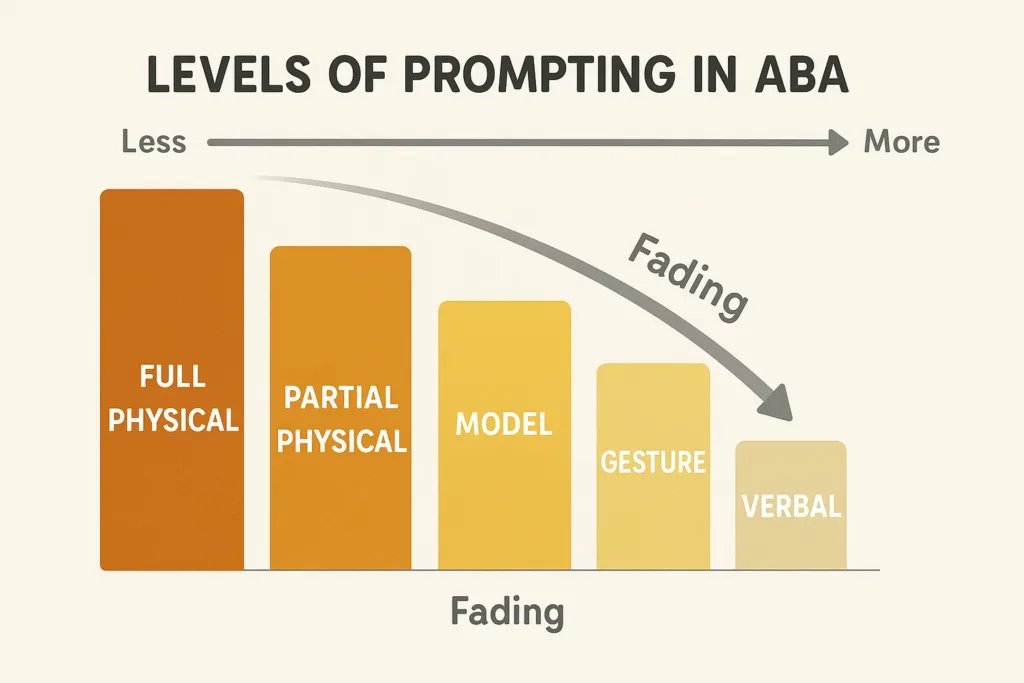

Prompting is an essential part of teaching new behaviors, especially when a client is learning a skill for the first time. A prompt is a cue or assistance given to help a client perform a correct response. As the client gains competence, these prompts must be faded to encourage independence — this is the heart of ABA prompting and fading procedures.

Types of prompts include:

- Physical (e.g., hand-over-hand guidance)

- Gestural (e.g., pointing to the correct choice)

- Verbal (e.g., saying, “Say ‘more’”)

- Modeling (e.g., showing the action yourself)

- Visual (e.g., picture cards or signs)

Mastering ABA prompting and fading ensures that clients don’t become dependent on assistance and progress toward independence. Prompt fading involves systematically reducing the level of assistance. For example, an RBT helping a child to wave goodbye might start with hand-over-hand prompting, then progress to a gestural prompt, and finally to no prompt at all. Teaching replacement behaviors and maintaining long-term success ties directly into our Behavior Reduction module (D-1 to D-6).

Prompt fading strategies include:

- Most-to-least prompting: Start with the most support, reduce over time

- Least-to-most prompting: Start with minimal help, increase only if needed

- Time delay: Add a delay between the SD and prompt to allow independent response

Common mistakes:

- Fading too quickly, leading to errors and frustration

- Not fading at all, creating prompt dependency

- Using inconsistent prompts across staff or sessions

Example: Teaching a child to tie their shoes might involve modeling each step and then switching to verbal cues as the child becomes more independent.

C-10: Implement Generalization and Maintenance Procedures

Skills aren’t truly learned until they can be used across people, settings, and situations. Generalization ensures that the client can apply learned behavior in different environments, with various people, and under varying conditions. Maintenance ensures that skills continue over time, even after direct teaching has ended.

Types of generalization:

- Stimulus generalization: Responding similarly to different but related stimuli (e.g., saying “dog” when seeing a new breed)

- Response generalization: Using different responses to achieve the same result (e.g., waving or saying “hi” to greet)

- Setting generalization: Performing the skill in new locations or with different people

Example: A child who learns to request juice in therapy should also be able to request it at home, in school, or at a restaurant. The RBT supports this by practicing the skill in multiple settings and with different instructors.

Strategies for promoting generalization and maintenance:

- Varying people, materials, and settings during teaching

- Reinforcing correct behavior in new environments

- Periodically reviewing mastered skills (maintenance probes)

- Teaching caregivers to prompt and reinforce skills outside of sessions

Mistake to avoid: Teaching a skill only in one context and assuming it will transfer naturally.

C-11: Implement Shaping Procedures

Shaping involves reinforcing successive approximations of a target behavior until the final behavior is achieved. It’s used when the desired behavior doesn’t occur at all and must be built gradually through reinforcement.

Example: A child who is nonverbal may first be reinforced for making any vocalization when requesting a toy. Over time, only clearer sounds like “ba” are reinforced. Eventually, only “ball” receives reinforcement. This progression — from vague approximations to the exact word — is shaping.

Steps in shaping:

- Define the terminal behavior (e.g., saying “ball”)

- Identify initial behavior that occurs naturally (e.g., grunting)

- Reinforce closer approximations over time (e.g., “ba” → “ball”)

Shaping requires patience, precision, and excellent timing. Reinforcement must occur immediately after the approximation and stop as soon as a new criterion is in place.

Common mistake: Reinforcing approximations for too long or inconsistently, which can stall progress or confuse the client.

RBT tip: Always consult with your supervisor on what approximations to reinforce and when to shift to the next level.

C-12: Implement Token Economy Procedures

A token economy is a system where clients earn tokens for displaying desired behaviors. These tokens are later exchanged for backup reinforcers (e.g., toys, breaks, snacks). This approach promotes motivation, delayed gratification, and clear expectations.

Components of a token economy:

- Tokens: Stickers, stars, points, or plastic chips

- Target behaviors: Specific actions that earn tokens (e.g., completing a task, using appropriate language)

- Backup reinforcers: Items or activities the tokens can “buy”

- Exchange schedule: Rules for how many tokens are needed to access reinforcers

Example: A 7-year-old earns one token for every completed worksheet. After five tokens, they can choose between iPad time, a snack, or extra playtime.

RBT responsibilities in a token economy:

- Clearly explain the system to the client

- Deliver tokens consistently and immediately after the behavior

- Monitor and document progress

- Ensure the backup reinforcers remain motivating

Mistakes to avoid:

- Giving tokens for undesired behavior

- Forgetting to follow through with the backup reinforcer

- Changing the token/reward ratio without supervisor approval

Token economies are widely used in ABA, especially in classroom, group, and home settings. They support structure, increase engagement, and help clients work toward larger goals.

Conclusion: Why RBT Skill Acquisition Is the Core of Success

The RBT Skill Acquisition domain (C-1 to C-12) is the beating heart of what RBTs do every day. Mastering RBT Skill Acquisition procedures equips technicians to help clients build lasting, meaningful skills. From preparing sessions to applying reinforcement, prompting, and teaching techniques, these twelve task items form the practical toolkit that every Registered Behavior Technician must master. Understanding reinforcement in ABA helps RBTs support behavior change ethically and effectively. Procedures like ABA prompting and fading, shaping, and generalization help translate skills to real-world contexts.

Whether you’re teaching a child to communicate, helping a teen build job skills, or supporting a client in developing independence, skill acquisition drives real, lasting progress. It’s also one of the most heavily emphasized areas on the RBT exam — and one of the most rewarding parts of the job.

By building fluency in procedures like discrete trial teaching, prompt fading, chaining, and reinforcement in ABA, you’ll not only pass your exam but become a more confident and effective practitioner.

Want to test your knowledge of reinforcement, prompting, and DTT? Take the Skill Acquisition Practice Test (C-1 to C-12) to apply what you’ve learned.